Editor’s note: The First Call contributor Bradley S. Klein served as a consultant to golf course architect Gil Hanse on the Worcester Country Club restoration project. He provides an inside look at the project.

WORCESTER, Massachusetts — At Worcester Country Club in central Massachusetts there is a sense of history everywhere. A plaque on the first tee, for example, reminds golfers that this private club 42 miles west of downtown Boston was home to the 1925 U.S. Open, the first Ryder Cup in 1927 and the U.S. Women’s Open in 1960.

Replicas of those respective trophies are in a museum-like display in the Tudor-style clubhouse. Another room honors Donald Ross, the designer of the 18-hole golf course who came here in 1913 and created a routing that has held up basically unchanged for more than a century.

The members of the original U.S. and British Ryder Cup teams still have their names adorning the wire-mesh lockers in the men’s changing room. And another plaque at the 11th tee honors Bobby Jones from that 1925 U.S. Open — not for having won (he came in second), but for calling a penalty on himself for a minor infraction at that hole that no one observed. “I might as well be honored for having walked by a bank without robbing it,” Jones observed.

Thanks to a restoration by Gil Hanse and his design team, Worcester Country Club can now lay claim to a golf course whose playing character befits its classical heritage. The work started in August 2023 and all but finished by the end of the year: new tees, completely rebuilt bunkering, fairway expansion, greens expansion and one entirely new green. What remains is only some tee reconstruction at the seventh hole following pond dredging that will take place later this year.

Total cost, inclusive of design fees, came to $3.7 million, paid for by a combination of on-hand capital and long-term borrowing, with no assessment or dues hike. The work took place without a complete shutdown of golf. Instead, parts of the course were closed to play sequentially, with golf variously limited to 15 holes, then 12, 10, seven, five and finally four by early November, when play would have effectively ended anyway. The few membership defections at the outset of the work have been more than compensated for by piqued interest and enrollments since.

“The membership inquiries are ringing off the hook,” club general manager Troy Sprister says. “Folks in Boston are rediscovering the beauty and value of golf in Worcester.”

It was something of a coup for the club to have landed the services of Hanse. He signed onto the job back in 2018 — despite a busy schedule of work at blueblood national championship courses worldwide — because “I was intrigued about the course and the possibilities of renewal. I saw some fascinating photographs of the place and thought we could make a major difference without blowing the place up.”

By then, Hanse’s restoration resume already included such Ross gems as Aronimink Golf Club in Pennsylvania, Brae Burn Country Club in Massachusetts, Lakewood Country Club in Colorado, Plainfield Country Club in New Jersey, Rochester Country Club in New York and Sakonnet Country Club in Rhode Island. Also, he had just signed on to do Oakland Hills Country Club in Michigan.

So, having worked on an artist’s oeuvre spanning three or four decades, as Hanse had, he had learned about subtlety and variety. When asked at an early interview at Worcester CC if he considered himself an expert on Ross, Hanse paused for a moment and then told the committee, “I’m an expert on what Ross did here.”

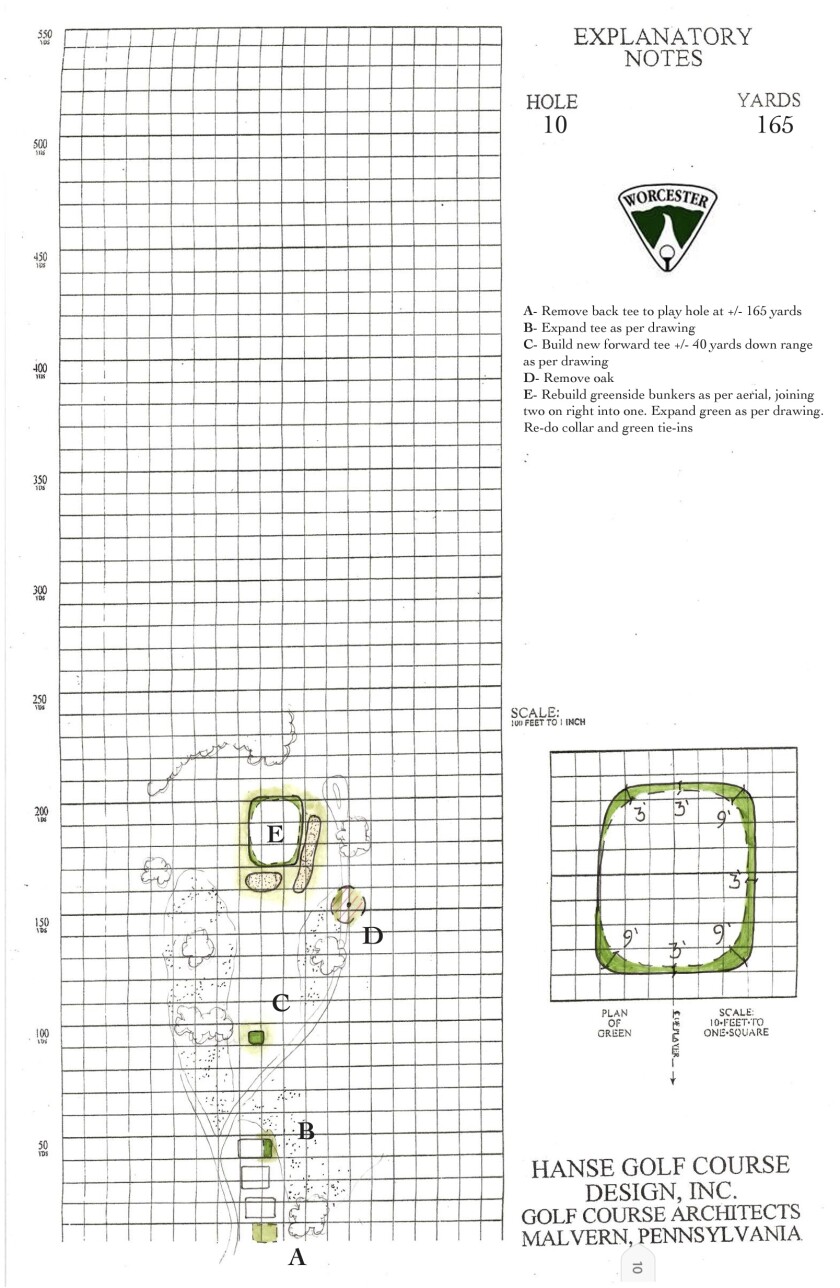

Full disclosure. I played a modest consulting role in the process, serving as a liaison between the club and Hanse’s design team. Much of that involved making sure the club’s representative expressed their concerns about budget and timing while allowing the Hanse design team to implement its vision of restoration without micro-management. It helps that Hanse relies upon crystal clear hole-by-hole plans conveyed on scaled graph paper — each box represents a 10-yard square. It’s a method that Ross relied upon as well from the 1920s on.

There’s no direct hand-written record of Ross’s plans for Worcester. However, back in 1913, he was a solo practitioner and had not yet assembled his trio of trusted aides — field designers J.B. McGovern and Walter Hatch and civil engineer Walter Irving Johnson. The raw data for envisioning this restoration came from a smattering of original construction photos, imagery and programs from the 1925 U.S. Open, and a high-altitude aerial from the mid-1930s.

The hole-by-hole sequence of the course had not changed over the decades. Extensive tree planting closed off many play corridors, however. Bunkers were shifted and invariably lost their flair. Greens shrank. Fairways had narrowed to accommodate the 90-foot diameter throw of single-row irrigation. In this way, Worcester had been transformed from an open, heathland style layout to a more conventional American parkland, with each hole narrowly ensconced in its own chute. One major design alteration occurred in the mid-1970s when Worcester's partially blind 11th green was raised by as much as 8 feet in the back, and flattened.

An initial effort to much of this had started in the late 1990s by architect Ron Prichard. Tree work, bunker renovation, greens expansion and the planting of some native fescue partially restored some lost character. But between the club’s hesitancy and lack of funding during some slower years, the effort stalled. By the time Hanse was called in, the club’s appetite had grown for more dramatic restoration. Still, it took a lot of internal club education and budget planning to prepare for what was in store.

It helped that Hanse’s hole-by-hole drawings easily translated into three-dimensional plans so that budget planning could proceed. Without precise volumes for cuts and fills, bunker construction, green expansion and new teeing grounds, planning for materials acquisition, work sequencing, labor, equipment needs and subsequent maintenance budgeting becomes little more than back-of-the envelope note taking. The precision that ensued from the original documentation of proposed work allowed for the work to proceed efficiently.

A key element was played by course superintendent Adam Moore (on the job since 2015), his lead assistant Scott Strong, and the entire maintenance crew. At some clubs, the superintendent shies away from the extra work that inevitably arises during restoration: expanded areas needing sod, bunkers that entail larger-than-planned areas of disturbance or newly discovered areas to be drained. Moore, by contrast, embraced each new task with an attitude of curiosity and interest that never flagged during the process.

Work proceeded on time despite rains that slowed things down on 14 out of 17 weekends. That washed out a couple of the club’s planned outdoor events but did not seem appreciably to impede the restoration. Tee work, focusing on new forward launch pads, had been done the year before, and tree work also had been in process for a few years prior to the major construction.

From the standpoint of aesthetics and playability, the restoration tied the features of the golf course together so that they became more integrated. Greens were expanded by 13% on average — from 6,880 to 7,780 square feet — and they now occupy the edge of their original fill pads and drip off into shortgrass or bunkers. Fairways were expanded from 28 to 32 acres to touch the entry point of bunkers and to make the ground game come alive. Trees were pulled back to establish more of a three-dimensional feel to each hole. And, across the site, interior vistas were opened up to a level that no one had seen for decades.

The par-70 layout also got stretched in two directions. The back tees went from 6,711 to 6,900 while the forward-most tees went from 5,434 to 4,907. The result is a more equitable set of teeing grounds for all classes of players.

Once Hanse and his lead designer, Jim Wagner, had solidified plans and budgets, it was up to their two associates, Kevin Murphy and Ben Hillard, to implement the bulk of the groundwork. One or both of them was on hand three to four days a week, in a shaping capacity, refining mow lines or simply making sure superintendent Moore and the MAS Golf team were in synch. They all stayed in constant touch with Hanse through a stream of emails, texts and calls. Work, once properly planned, does not need a lot of formal meetings.

Hanse didn’t just keep in touch while busy elsewhere in the country. On a dozen or so occasions he was on sight, usually on a small dozer or excavator, keying in crucial features. The most dramatic came at the par-4 11th green, the scene of that 50-year old raised green that stuck out like a sore thumb. The back was lowered by about 8 feet, down to what was presumed as original grade.

Then came a complete rebuild of the surface, with Hanse crafting a new putting surface in a stint of intense work that allowed him to avoid any meet and greets or video documentation. He’s happiest when geared up in the cab of a machine with his ear buds in, listening to a playlist heavily tilted toward the “Grateful Dead.”

It’s always a strange process to watch the entirety of course restoration. Here was a course I thought I knew well and had certainly admired. And yet what has been revealed and opened up during five months of work has made the place feel like an entirely different and much more interesting golf ground. What started in 90-degree-plus heat ended up in temperatures in the 20s. It’s easy for golfers to overlook how much physical labor is required to turn the clock back on a golf course.

Now, Worcester sports fairways not only expanded but joined at the hip in a way that opens up the entire site. The bunkers stand out and help orient players while also serving occasionally as a surprise for those who hit the ball too far or offline. The drop-shot, par-3 10th hole was actually shortened. The approach into the new green on the longish par-4 11th has been toughened by creating a short carry bunker in front that extends across, but still leaves a 15-yard ground game entry. And the memorable short par-4 18th now stands out even more for its sharply bunkered green.

The course reopens for member play in the spring of 2024. That’s when the word will start to spread, across town all the way to Boston. Another Ross gem has been polished.