Editor's note: Richard Mandell is a golf course architect based in Pinehurst, North Carolina. His firm, Richard Mandell Golf Architecture, has designed more than 75 golf course projects in 15 states and China, and his work has earned 31 different awards and accolades. "Principles of Golf Architecture" is Mandell's fourth book.

—————

THE PRINCIPLE OF PAR

Par: The score a scratch player would expect to achieve on a hole under normal course and weather conditions, allowing for two strokes on the green.

There are actually two definitions for par in the USGA Rules of Golf. The above is from its Rules of Handicapping section. It’s universally understood by all golfers and is a target of sorts for all skill levels. The variable that identifies the different par types (3, 4, 5, and even 6) is yardage.

Before the twentieth century, “bogey” was used to identify the target score for recreational golfers and “par” became the ideal score on a given hole for more serious players. In 1911, par was officially introduced by the USGA as the score to beat and golf holes were distinguished in the following manner:

- Par3 for men up to 225.

- Par 4 for men 225 – 425 yards.

- Par 5 for men: 426 – 600.

- Par 6: 601 yards or more.

These numbers were slightly revised in 1917 and re-defined in 1956 when the longer distance for each hole type was increased and yardages for women were established. In 2020, hole distances were updated once again:

- Par 3 for men up to 260 yards; women: 220 yards.

- Par 4 for men 240 - 490 yards; women: 200 – 420 yards.

- Par 5 for men: 450 - 710; women: 370 – 600 yards.

- Par 6: 670 yards–plus ; women: 570 yards or more.

The definition in the “General Playing Rules” of the USGA simultaneously addresses both par and bogey without actually defining either. Rather, the USGA refers to how a player scores in comparison to a “fixed target score” set by the committee in a competition. The fact that it’s specifically defined as it relates to handicapping but not specifically defined in the General Playing Rules is the tell-tale sign that par can be somewhat of an arbitrary goal for golfers; one that changes on a personal level.

SHOP: Purchase "Principles of Golf Architecture"

For a golf course architect, par designations mean that for every par-3 hole that’s designed, one only needs to find a teeing ground and a green site. A par-4 hole necessitates a teeing ground as well as one landing area and a green. A par-5 hole necessitates two landing areas in addition to a teeing ground and green site. The Principle of Par challenges the golf architect to consider the basic needs of each type of hole within an overall golf course routing and how those requirements are applied to the ground.

In the day-to-day playing of the game, though, the number assigned on a scorecard to a hole’s par is somewhat irrelevant to the playing of the hole. The knowledge that a hole may be a par 4 or a par 5 doesn’t technically help us swing the club any differently when faced with a 470-yard hole. It shouldn’t change one’s strategy either. But it does. Par designation does not change one physical element of a particular hole, yet take a stroke off the scorecard and it becomes that much more difficult to many golfers.

I remember playing a junior tournament at Tamarack Country Club in Greenwich, Connecticut, in 1985. Two of the first four holes were par 4s of 446 and 463 yards. Looking at the scorecard, prospects did not look good for me (I wasn’t very long but always down the middle). My little blue Ram driver just didn’t have it and I didn’t have another club to reach either hole in regulation. So I played them as par 5s and made four on both holes, doubling down on my focus when confronted with fewer shots designated on the scorecard. I played within myself to ensure that I could take advantage of my short game and was successful getting up and down each time.

I then made bogey on the 491-yard par-5 13th hole. Although I had a whole extra stroke to get in the hole, I still made a six. Not only did I let my guard down, I was much more aggressive, lulled into the false perception I had an extra shot to play with. The reality was that I didn’t because my final score was the accumulation of 18 holes worth of shots being compared to the other golfers in the field.

Yet the par assigned to each hole changed my thinking. Other than the number on the scorecard and a few more yards, those three holes couldn’t have been more similar. None of them had water and all of them had openings in front of the green. Regardless, the prospect of a number on the scorecard greatly affected my strategy, focus, and subsequent results. Although par 3s, 4s, and 5s are clearly defined by distance, the anguish the Principle of Par brings to the golfer is what makes the game so vexing.

There are basically three ways one can look at their own score after they hole out: the actual number of strokes; whether one’s effort resulted in being under, even, or over par; and by comparing scores with the people you were playing with or against. In that case, the number of strokes does not matter. All that matters is if you won or lost the hole.

That third approach — widely known as “match play” — is one way to minimize the influence of par on the scorecard. The difference between match play and stroke play (also known as “medal play”) is that the golf course is solely the playing field in match play. Therefore it has absolutely no bearing on a one–on-one match-up. A golfer’s score is only being compared to their opponent’s score, not to multiple golfers playing that day or even the course.

Match play frees our mind of the clutter involved in posting a number on a scorecard after every hole. Whether a 275-yard hole is a par 3 or a par 4 is irrelevant. In fact, these “half-par” holes can accommodate a variety of skill sets much like a boxing match between two fighters with contrasting attributes. Will the one who can drive such a hole come out on top or will the one who can take dead aim with a wedge be victorious?

Freedom from the shackles of par has another liberating effect through match play: Whatever gamble the golfer takes will only affect them on that specific hole. One won’t carry the weight of their decision for the remainder of the match. In stroke play, the burden of par grows heavy when the prospect of making up for a quadruple bogey on the previous hole is forefront in one’s mind. Yet in match play the cost was just one hole. The golfer’s focus can move directly to the next hole with the possibility of gaining back the previously lost one.

When the idea that a "championship course" must be 7,000 yards long gained a foothold in the golf course development world, so did the matching standard par of 72 strokes, typically divided between each nine. The Principle of Par took a turn for the worse when architects ensured their design work met those thresholds, regardless of site characteristics. To this day, that standard is strong in the minds of developers, architects, and golfers.

When I redesigned Keller Golf Course in Maplewood, Minnesota, and swapped par for the ninth and tenth holes, the move caused initial heartburn for the pro shop staff. For many years, Keller had two nines of 36. But when we converted the ninth to a par 4 and the 10th to a par 5, the nines became 35-37. Despite the overall par remaining at 72, this change brought about much debate, centered solely on the fact that the golfers who only played nine-hole rounds would feel slighted if the front nine didn’t play to a par of 36. Management felt that if the par was less, they couldn’t charge as much for green fees. Eventually, common sense overcame emotion and flawed economics. Not only was safety improved by spreading out the ninth and 18th greens (by shortening the ninth), the architectural value of each hole was strengthened as well by converting a very short par five into a par four and transforming a boring par 4 into a risk-reward par 5.

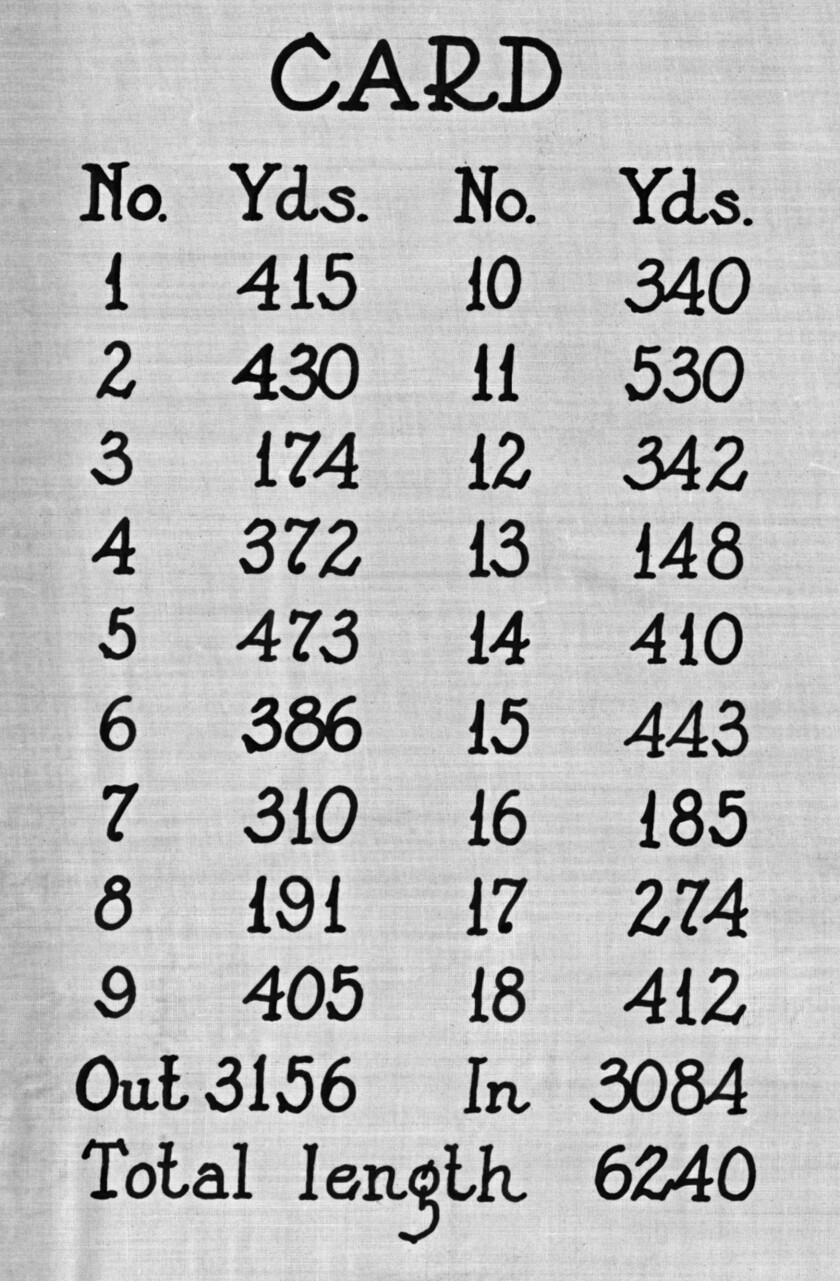

Donald Ross almost never assigned par to any of the holes he designed. From Ross’s earliest layouts, such as his 1915 routing of Oconomowoc Golf Club in Wisconsin to one of his very last projects, Raleigh Country Club in North Carolina in 1948, only the hole number and yardage were denoted on Ross’ plans. His separate golf hole drawings showed a number followed by “yards” with a period at the end. To this day that period seems to say, “don’t worry yourself over the required number of strokes. Just play.” He was very cognizant of the need to find the best features and layout the best holes without mucking things up with distance classifications.

Ross would probably be appalled at judgments rendered about a hole’s quality based on its distance. He might just argue that a short par four should never be judged any less of a hole than a par four that measures one-hundred yards longer. The shorter hole could be chock full of a variety of challenges based on natural features found along the way and its distance may not hinder any number of golfers from trying numerous shots in the spirit of the Principle of Challenge. The longer hole, though, may be a bore and a trudge from start to finish, avoiding those same natural features because they may not tie into the “championship” distance. The Principle of Difficulty is in full wearisome bloom when length overrules nature.

Simply put, the Principle of Par should never be in the forefront of an architect’s mind. First of all, when routing a course it takes more space and earthwork to create additional landing areas. In addition, if one is conditioned to create a “standardized” par 72 course or to evenly distribute strokes between each nine, natural landforms may be bypassed for more manufactured features. For example, adding 50 yards to a 450-yard par 4 to create an additional par 5 may require the substitution of a great natural green location with a less-than-stellar one, bringing the overall experience down a notch in the process. Without focusing on such a standardization, the architect is free to seek out the best natural attributes for the most memorable golf features.

The USGA’s rules of golf define par only as it relates to handicapping and doesn’t mention the word by name when discussing competitions. That should scream loudly to the golfer that par isn’t intended to affect the everyday playing of the sport. Therefore architects should not focus on the Principle of Par as a design tool nor should golfers look upon it as a goal to grind over (obviously easier said than done).

Although a golf course should be a single unit held together through the Elements of Design, individual shots are what we remember most. We forever recall the one shot that keeps us coming back and when we recount that shot in our mind, the score for the hole is often secondary. What is prime in our mind is the lie, the yardage, the club in our hand, contact with the ball, and its path until it stops, concluding with our own self-declared brilliance in orchestrating it all.

Golf architects should always find the best holes possible to create the most interesting and fun shots, without a pre-conceived scorecard driving design decisions. Stringing multiple shots together makes the journey that much more enjoyable and the storytelling that much more vivid. I believe the quirks and challenges of golf course architecture can be more freely appreciated by highlighting the land instead of emphasizing the importance of numbers on a scorecard.